Google pulled a fast one on us.

There are few web services I love(d) more than Google Photos, which enables you to back up unlimited images to the cloud.

With Google Photos, there’s no need for clunky hard drives. No worrying when you drop your iPhone in the river—and all of those adorable photos of your two-year-old with it.

Google Photos also plays the role of personal scrapbook maker. The application automatically categorizes your photo by date, by location, even by face.

And the kicker? It’s all free. (Or was anyway.) I know, I know: as the Silicon Valley saying goes, if you don’t pay for the product, you are the product. I’m well aware that Google is harvesting my personal data to sell to advertisers. But…unlimited photo storage? That’s hard to beat.

But…that’s all over now.

A few weeks ago, Google announced that it would no longer offer unlimited free storage on Google Photos.

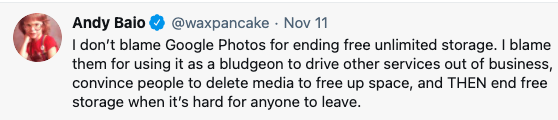

People were less than thrilled:

They felt duped. Google had lied to them! Google had gone back on their word! They said Google Photos would always be free!

The thing is: Google never lied to them. Google never explicitly said that Google Photos would always be free. That was an imagined promise. An assumed commitment.

But that didn’t stop folks from getting upset. They felt like it would always be free. It was an expectation they had come to rely upon. And so, Google’s announcement felt like a betrayal.

This is such a great example of one aspect of accountability we often get confused–we assume that we are only accountable to follow through on what we explicitly agree to do.

But to ensure a maximum degree of workability, we actually need to go beyond that baseline definition. We need to be accountable for what we implicitly agreed to do as well.

A colleague asks you to review a document they’re working on. “Sure,” you say. “I’ll have a look.”

Now, what the colleague meant by “review” goes unspecified.

The colleague has in mind a thorough review. You had in mind a quick once-over, which is all that you have explicitly committed to and all that you have time for, anyway.

To really be accountable in this situation, you’ve got to account for what the colleague assumes you will do.

“But that’s not fair!” you say. “How can I be held accountable for what I didn’t even agree to the first place!?”

That response is valid. But it comes from a place of being “right.” Of what’s “fair.” It turns out that “fair” and “right,” have little do with what actually works.

The cold, hard truth is: if we don’t acknowledge the reality of what others expect of us, we’re going to get a lot of wires crossed. This makes us less efficient, less effective, and sows seeds of frustration and resentment.

The remedy to this ambiguity and discontent isn’t easy, but it is simple: we need to make the implicit, explicit.

Whenever we’re in conversation with someone and come to an agreement, we need to not only call out what we’re going to do, but what we are not going to do. To be clear: that doesn’t mean we need to actually do something just because others expect it. But we do need to address that expectation.

That may look something like: “I’m happy to have a look at that document, but I really only have time to do a once-through. If you need someone to really comb through it and give you feedback, it would be best to ask someone else.”

It can be an awkward process at first, but leads to more workability and fewer headaches down the road.

Reflect for yourself: What implicit agreements are active in your life? Where have you agreed to something implicitly? What next action can you take in order to make the implicit, explicit?